Jordan Peterson Needs to set his Metaphysical House in Order

A quick word on the “Surrounded” Jubilee video

Jordan Peterson: The basics

In case you don’t know anything about Jordan Peterson, I’ll quote myself from my Denison Forum article (but feel free to skip if you already know his modus operandi):

“Dr. Peterson is a Canadian clinical psychologist and professor of psychology. He authored Maps of Meaning in 1999, which, although well-received, did not launch him into intellectual stardom. He rose to prominence in 2016 for critiquing a Canadian law that would have [supposedly] compelled people to use transgender gender pronouns.

Around the same time, Dr. Peterson uploaded a series called The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories, which garnered tens of millions of views. In them, he identifies psychological principles that transcend culture and history.

Dr. Peterson charismatically plumbs the depths of biblical stories, like the tale of Cain and Abel, for thoughtful wisdom. He calls biblical stories ‘meta-truths’ because they represent patterns of life so well that he thinks everyone should attend to them to live a more purposeful, orderly life.

Dr. Peterson then began a tour of public speaking and podcast appearances while continuing his YouTube series. He wrote the massively successful self-help book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. In 2020, for a year, he stepped away from public life due to health complications and an addiction to benzodiazepines. He returned to public life after completing Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life. In 2022, he joined the conservative media platform The Daily Wire.”

As a former Peterson fan…

With the basics covered, I can speak personally. I believe Peterson is (or at least was) a force for good as far as he goes. He advocates for thoughtful responsibility and a psychological approach to living a purpose-driven life.

His emphasis on personal, individual responsibility makes him a leper among critical-theory, postmodern, and neo-Marxist academics. That said, I thought of him as quite classically liberal until he joined the Daily Wire.

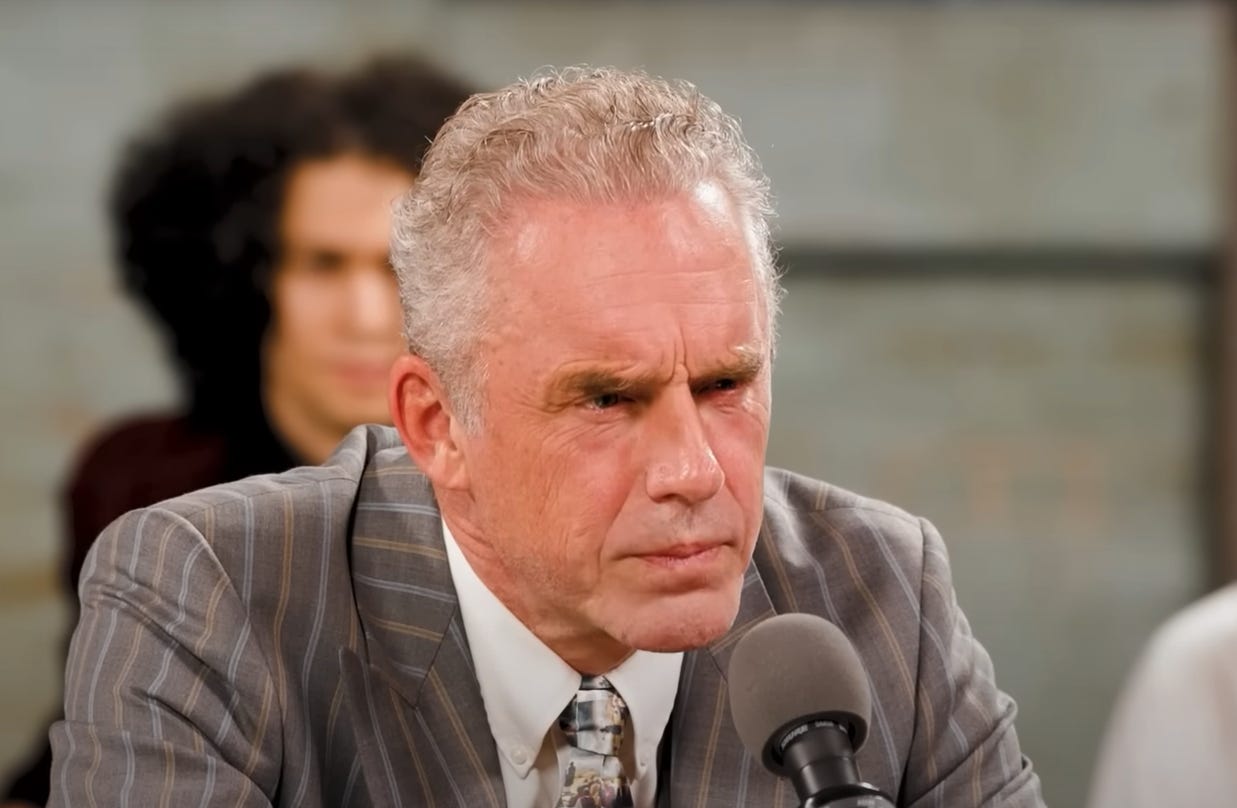

We can’t expect public intellectuals to be an expert in every field. When he stuck to his existential, Jungian, and psychology-based analysis of sacred Western texts (including Dostoevsky, the Bible, and Disney’s Pinocchio), he stepped with confidence, albeit with his trademarked strained “thinking hard, angrily” expression. As he has stepped away from this center, he has faltered.

Recently, he joined a confrontational debate show “Surrounded” by the YouTube group Jubilee. He opposed 20 lay/influencer atheists. Peterson found himself going viral once again, but not for interesting and principled reasons. Instead, his inability to give coherent remarks about God came into mocking view. Also, the fact that he denied claiming to be a Christian, when the video was originally titled “One Christian vs. 20 Atheist,” raised a few eyebrows. Quickly after the video went up, they changed the title to “Jordan Peterson vs. 20 Atheists.”

Suffice it to say, Substack has been having a heyday. As a former Jordan Peterson fan, I couldn’t help jumping in.

I haven’t kept up with Peterson recently. I haven’t read We who Wrestle with God (I’ve heard bad things), and haven’t paid DailyWire to watch his New Testament lectures. So my knowledge of him might be a bit outdated. As such, I’ll primarily focus on the video, and I’m only going to focus on one part of the Jubilee debate, Peterson’s first “claim:” “Atheists reject God, but they don’t understand what they’re rejecting.”

In what follows, I’ll pick out a few fallacies, where he goes wrong, and try to get clarity on where the atheists and Peterson missed each other like ships in the night.

A handful of fallacies

From the outset, I’m going to call what Peterson means when he says God “P-God” for clarity, and “God” will refer to the traditional view of God as a maximally great being. I want to take Peterson as charitably as possible. Setting up a stand-in concept for what he means when he says God will help.

As a former trainee for the Catholic priesthood turned atheist, the first debater says he knows what he’s rejecting. He immediately charges Peterson with the “No true Scotsman fallacy.” This fallacy refers to when someone makes a generic claim and dismisses valid counterexamples by saying the examples aren’t “really” a part of the group they’re discussing. For example, I could say, “All Scots like Guinness.” To which you might reply, “Well, I know my friend George, who grew up in Glasgow and lives there still—he doesn’t like Guinness.” I could, fallaciously, reply: “Ahh, see, George isn’t really a Scotsman then.”

This seems correct. Peterson is saying people who claim not to believe in God don’t really disbelieve in God—they just misunderstand their own position. Peterson is already off to a rough start, essentially making a fallacy before he begins.

Dr. Peterson admits his claim is generic, “just like the atheist’s claim that there is no God” is generic, as he says. But, as we’ll see, this is false. Atheist’s claims are usually not generic; many of them make narrow claims about reality.

Thankfully, early on, Dr. Peterson specifies Claim #1. He says, roughly:

Atheists (tend) to have a reductive notion of “God.”

Atheists (tend) to have rejected P-God because they’re hurt by religious institutions, Christians, or even P-God himself.

Already, against the first debater, Peterson psychologizes his arguments. He implies that there must be some psychological reason that the debater hadn’t properly aimed at discovering P-God. While (1) and (2) might be correct, they’re not technically arguments against atheism. Point (1) may not apply to the debaters he’s facing. Point (2) makes another fallacy. To see why, imagine an atheist saying, “Well, religion tends to make people happier. So you’re just a Christian to be happy, not because you think it’s true.” This may describe some, many, or even most Christians, but it’s invalid as an argument against the truth claims of Christianity. This is called a “genetic fallacy.”

Not off to the best start. Peterson is not usually clear or rigorous, true, but he’s not unintelligent. So why does he make so many obvious missteps? Read on.

The crux of the issue

Peterson tries to make his first point. He refers to the story of Moses seeing P-God’s back, unable to see his face and glory, otherwise Moses would die. Peterson interprets this as meaning P-God is ineffable and unknowable; he’s something to be explored, but never discovered. Peterson doesn’t explicitly say the next part, but it’s implied that if P-God is unknowable, it’s technically unrejectable. This is bad epistemology, making his claim “atheists don’t know what they’re rejecting” trivially true, but we’ll let it slide for now.

So, we have the first aspect of P-God defined: “[Experience of P-God is] a pinnacle experience and … people in their finitude have to be shielded from a comprehensive vision of the basis of reality.” So, P-God is the basis reality that cannot be comprehended. That’s actually an acceptable idea, with caveats, for most Christians.

However, it seems to me that an atheist could agree with this claim, while rejecting a more formal definition of God. For example, they might,

be a naturalist (affirming the causal closure of the universe),

believe that if there’s no reason to believe something, you can deny it, and,

be agnostic about the fundamental nature of reality.

Together, these views would allow someone to believe there’s no God (given 1and 2) and (3) would allow them to accept P-God. In other words: One can accept (or be agnostic about) P-God while simultaneously rejecting God.

The first debater suggests this route, responding to Peterson by saying, “I think you have a reductive notion of atheists.” Many of the following debaters will make this point as well. This argument plays out over and over, and Peterson denies, over and over, that P-God and God are distinct concepts. This is the crux of the issue, in my estimation. Peterson’s lack of a coherent metaphysics is one of the root issues of his incoherence about theism.

Problem: Peterson (lack of) metaphysics

Peterson’s beliefs and claims, as an existentialist, Jungian, psychologist, underdetermine metaphysical assertions. In other words, Peterson’s core beliefs (and expertise) are compatible with mutually exclusive metaphysical views: Naturalism, transcendental idealism, Russellian monism, common-sense realism, materialism, and more. As a loose existentialist and, broadly, a loose pragmatist, he at least does not care about metaphysical claims. And theism is, to most, at least a metaphysical claim.

Peterson might be a metaphysical anti-realist if he gave it enough thought. This is the view that metaphysical claims are always false in some way, because they wander away from linguistic referents. Let’s unpack this idea as I understand it.

The argument roughly goes like this. Language relies on meaning, and meaning depends on experience. Therefore, language cannot talk about the world outside of experience. But this is precisely what metaphysics claims to do. Therefore, metaphysics is always false in some way. Peterson has suggested as much in the podcast with Dr. Christopher Kaczor and Dr. Matthew R. Petrusek. Metaphysical anti-realism is compatible with P-God, but not with God—the classical view of him.

If Peterson isn’t a metaphysical anti-realist, then he’s probably a noumenalist—meaning he believes that the physical and mental are unified in the fundamental nature of reality, but that fundamental nature is by definition inaccessible to us. This would leave us with a Kantian view of God; God is a being necessary for us to affirm for moral concepts and freewill, but is by definition noumenal (unknowable). That seems to overlap with Peterson’s worldview quite well.

If I were a betting man, and I am at the odd Texas Hold ‘Em game, then I would bet Peterson would choose some version of anti-realism or Kantian noumenalism as his metaphysical stance. (I could also see a common-sense realism blooming in light of his repulsion for anything with a whiff of nihilism.)

An alternate route in William James

Perhaps Peterson would go the way of William-James, and commit outright to pragmatism. I’m not familiar with James’ philosophy, but I know philosophers debate James’ metaphysics because he was, indeed, often confusing. However, even he was more rigorous and interesting than Peterson on these ideas.

So, what does James’ pragmatism look like? The SEP contribution about James by Goodman Russell summarizes: “Truths are goods because we can ‘ride’ on them into the future without being unpleasantly surprised.” Russell quotes James,“‘On pragmatistic principles,’ James writes, ‘if the hypothesis of God works satisfactorily in the widest sense of the word, it is true.’”

This James-esque view makes sense. As a clinical psychologist at heart, Peterson undeniably views reality through the lens of the human psyche. When Peterson lectures to psychology students, this doesn’t come up, because he’s limiting himself to the realm of psychoanalysis with a sprinkling of existentialism. Fine and dandy. But in this debate, Peterson isn’t making a psychological point, he’s talking about God!

Peterson could adopt noumenalism, pragmatism, common-sense realism, or any number of positions, then explain his belief in God based on his view of metaphysics. The problem is, Peterson doesn’t explain any of this. This makes his articulations confused, and forces him into erratic fallacies.

This lack of basic metaphysics is perfectly fine for normal folk, but it leads to problems when he tries to argue metaphysical stances, like debating whether God exists.

The Jubilee train wreck

So, here’s what happens in the Jubilee debate. Peterson takes up the stance of rough-and-ready pragmatism, without metaphysical clarity. Consider the following two statements.

I live as though there is a computer in front of me.

I affirm the existence of a computer in front of me.

In my mind, to Peterson, (1) and (2) are identical statements. Each one exhaustively entails the other. They may appear to be two different claims, but they are the same.

Let’s extrapolate this out a bit to include the rest of the argument.

(2.1) I live as though God were real.

(2.2) I affirm the existence of God.

The debaters immediately caught onto the position that Peterson believes (2.1) and (2.2) are identical. But, there’s another layer to the confusion. The atheist debaters often argue for the following statement’s compatibility:

(3.1) I live as though P-God were real

(3.2) I deny the existence of God

The debaters are (3.1) and (3.2) seem compatible. Peterson either expands on P-God, or reiterates that P-God and God are the same. But he misses the point. Some atheists even seem willing to hold that “living as though” and “affirming the existence of” are distinct, and indeed, accept the existence of P-God (whatever P-God’s “existence” might look like, see his metaphysical disambiguation above)—but not God.

Greg, my second favorite atheist behind from Zina (I’m relieved that Peterson picked her for extra time), states the problem with astounding clarity. I’ll just quote Greg’s entire spiel:

So, I feel like you're getting at this idea of polysemy where we have multiple related meanings for a word, right? Like for example, a famous painting can be emotionally moving in that it changes my emotional state. And when I was on the highway coming here to the studio, I was physically moving. I was changing my position.

If I said, “I believe the Mona Lisa is very moving.” And you said, “You don’t really understand what you’re saying. It’s nailed to the wall.” I would say that you;re the one who doesn't understand what I’m saying, not the other way around.

He then defines God in a well-put maximal being type-way: “God is [an] omniscient, omnipotent, agentic, supernatural being, who sent his son down and [does] miracles…” This outlines a dogmatic, philosophical, Christian concept of God—which most people mean when they talk about God in a debate setting. Of course, this philosophical definition is like the black and white borders that the Bible and life experience fill in with color. It’s like saying the Mona Lisa is a collection of oil on a white poplar panel and leaving it at that.

Nevertheless, something like Greg’s definition is minimally present in all monotheistic religions. And Peterson can’t seem to grapple with it, because he lacks even the simplest metaphysical stance.

Wrapping up with two more of Peterson’s claims

Peterson makes a couple of other interesting claims in this section.

(I) If two people have mutually exclusive views of P-God, language is impossible.

I also happen to think that, without God, language would be impossible. Put another way, I take the metaphysical possibility of language as evidence for a unifying cohesion of a God-like explanatory force behind reality. The argument would be similar to the argument from design (the teleological argument).

It’s hard to see how this makes any sense, though, with P-God. If P-God is so ineffable, how could he ground the effability of language? Additionally, it’s hard to imagine P-God being causally efficacious enough to make language work. In other words, what about the nature of P-God explains the way language works?

(II) P-God is the voice of conscience within

This thought of God as the source of conscience is common. The moral argument for God’s existence makes a claim from the intuitive strength of nomic ethics (law-like morality) that God, as a lawgiver and creator combination, must exist. But, I suspect Peterson means something more like Kant’s view here.

Here’s my theory on why Christians have a difficult time with Peterson. Christians usually affirm God and P-God, identifying P-God with God. In other words, Christians affirm the statement *God* is the voice of conscience within, but find that statement meaningless if *God* refers only to P-God, and not God. But since Peterson doesn’t clarify the difference between God and P-God, he lures Christians into a false sense of comradery.

In other words, Peterson is essentially agnostic + Christian (P-Christian?), but he obscures the former part. His exploration of P-God as the voice of conscience might intrigue Christian thinkers. Fair enough. But atheists and Christians alike must remember that he’s not a metaphysical theist, only a P-theist.

This is why I believe atheists have historically done a better job at confronting Peterson’s convoluted non-theism. (However, as usual, Richard Dawkins is the atheist’s version of Christian fundamentalist, seven-day creationists.) Alex O’Connor, in this podcast, does the best job of confronting Peterson on his wishy-washiness. If twenty average atheists can so handily point out Peterson’s confusion, he needs to shore himself up.

If I may say so, Jordan Peterson needs to set his metaphysical house in comprehensible (much less perfect) order before he criticizes atheism.

Peterson is neither a trained philosopher nor a theologian. As a public intellectual, especially as a talking head of Daily Wire, he’s called upon to talk about things with conviction of which he has no expertise (climate change, for example). It so happens that Peterson is a much, much better psychologist and existentialist lecturer than he is a debater, political pundit, philosopher, or theologian.

I hope he regains his sense of self, discovers the true Christian Gospel, and finds a meaningful relationship with the person of Christ.

Thanks for reading.

Soli Deo Gloria

I was waiting for someone from our circle to come out and talk about this. Thanks for delivering.

I find it absolutely hilarious, as a Catholic, that Peterson has done much to curry favor with the religious world, but it seems that this debate has lost him most of his credibility and goodwill, at least with the Catholic world.

Something that I believe is worth mentioning here is that Jungianism is totally inextricable from nearly all of Peterson's claims about anything. He approaches everything with a Jungian lens, and therefore something should be said about Peterson's interpretations thereof.

Jung seems to affirm the existence of ubiquitous universals that each have different modal representations in accordance with the epistemic framework of people. In other words, there are universal things in the world that we are attuned to, and expressions thereof are products of our particular situation in the world. When Peterson says that atheists don't know what they're rejecting, he's trying to lure them into the trap that there is a pervasive attunement to God (as a universal) that exists for every person--the "God-shaped hole," so to speak. Sure, at it's most basic level, he might be trying to do the old Aquinas trick wherein people must concede that there at least logically must be space for God as a primum mobile, or at the very least an explanatory heuristic.

For Jung, and for Peterson, all particulars are towards truth, but ultimately fall short from it. God is true, but God qua Christianity is not necessarily true, but rather towards the higher order truth of God as such. For instance, Jung made the radical claim that the kenosis of Christ is a particular, culturally situtated manifestation of absolute nothingness; absolute nothingness as a metaphysical category can be observed across cultures such as in Zen Buddhism. It is not so much then that the kenosis is truth, but absolute nothingness is.

The deeper point I am trying to convey is that language is not essential for delineating facts about the world for Jung; everything is symbolic in nature, and symbols are a priori. Language is completely heuristic, and it serves to function as references towards more complex truths about the world. Peterson believes this, and so he lacks the rigor to speak about the semantics of his concepts. To him, everyone has an answer to the God question that they are simply unaware of insofar as they are incapable of expressing it adequately.

I feel it is a little bit disingeuous to chalk up Peterson's failures in this debate to merely semantic confusion, but of course, I am not disputing that Peterson's absolute L in this debate. I think Peterson ultimately fails also because he is philosophically homeless and spiritually bankrupt. He has an idea of truth, but he has only pursued it insofar as he can say things about it non-committally. It's almost like he anticipates failure, and he's just waiting for the right kind of failure to come along for him to absorb into his middling worldview. (It's funny; this failure came when Zizek absolutely wiped the floor with him. Yet he still hasn't read Hegel. Maybe fraternizing with communists is bad for his paycheck with conservative media.).

On that note about James, I do believe that Peterson swings more thoroughly towards Feuerbach more than James--God is a product of projection, and is thus innately anthropological. It is not so much that we believe in God because it is necessarily pragmatic to do so, but rather we believe in God because we existentially find ourselves in a situation in which we must be ordered towards something that is larger than us, yet comprehensible in some capacity--a symbol, in other words.

The grand irony is that this agnosticism informs Marx's view of ideology in his material dialectic, wherein it is, to speak loosely, a necessary evil for the status quo to function. (But, as most of us have observed in Peterson vs. Zizek, Peterson has never read Marx).

Peterson is most definitely an agonstic because he is unable to universalize the very particular soteriology of Christianity. As a metaphysician, he is a cautionary tale for anyone that decides to put an unearned emphasis on universal categories whilst discounting the particular modes these categories manifest in. His theology is at best benign, but far from the complexities of Jung.

On another note, when I saw Zizek at Edinburgh, Zizek mentioned that Peterson indeed challenged Zizek to a round 2 and has invited him multiple times to his podcast. Zizek has rejected each time and eventually stopped responding altogether. He says that Peterson was "no longer interesting" and is generally "much stupider."

I am in full agreement with you that Peterson lacks a coherent metaphysics, and because of this lack he is out of his depth with traditional atheist-theist debaters. But I think his primary problem is not a lack of metaphysics, but a lack of wisdom, in a very precise sense that I’m gonna explicate.

I think the issue here at least in part is that Peterson’s hero Jung was never a fan of metaphysics. As far as I know, Jung read little philosophy after Kant, who probably exerted the strongest influence on Jung when he derived his theory of the archetype. As Kobe gestured at this, Jung did believe in universals, and that particular meaning, form, and symbols are all imperfect instantiations of the universal within particular culture and historical situatedness, and this is Kantian insofar as the source of the intelligibility of the universals do not lie beyond the agent in contact with the particulars.

Jung’s dismissal of metaphysics is similar in spirit as the later periods of Husserl (In Crisis in particular) and other phenomenologists that followed (particularly Heidegger and Merleru-Ponty). The charge is essentially that European scientists and metaphysicians have forgotten the place from which their philosophizing, scientizing, and intellectualizing originate. For Husserl, for instance, the originating place is something like the constituting acts of consciousness. I take it that the phenomenologists’ central point is that people have tried to reach some essential and reductive source of intelligibility of the world that is totally beyond the place from which the theorizing happens, that this forgetfulness has produced a variety of problems for societies plagued with the European metaphysics, and that to remedy this it is up to the philosopher to go back to the source and clarify it structure again. As far as I see it, however Husserl complexifies his categories and the constituting activities of consciousness, the picture he puts forth is still largely Kantian in origin. Jung’s dismissal of metaphysics is first a foremost an influence from Kant and were similar in orientations as the phenomenologists in diagnosing the problems of European society as a kind of forgetfulness of the origin and source of intelligibility. Similar to Husserl and other phenomenologists, Jung’s solution is to clarify, work out, and table the structures of intelligibility (most prominently in the theory of archetypes and personality types), with the crucial difference that he tries to clarify the structure and constituting activities of the unconscious and how it is rooted in the greater reality of what he called the collective unconscious.

But unlike Husserl and other phenomenologists (maybe with the exception of Heidegger), Jung blends the Kantian epistemology with a Gnostic mysticism. And I think this is where Jung’s metaphysics and systematization really blow up. At least in Kant and the phenomenologists, they were careful in deriving and tabling the categories and detailing what kinds of constitution give rise to the rational intelligibility of the world. As soon as this got blended with Gnosticism, it all went down the drain. An example is Jung’s interpretation of astrology and alchemy. He didn’t think of these as pre-modern scientific efforts at all to study and document the movements of the heavens or the matters but the manifestations of genius mystics who have projected their unconscious (which is always a partial instantiation of the collective unconscious) activities onto the physical world in order to purify and transform the psyche. This transformation consists in the nested twofold activities of on the one hand individuating the personal psyche from the collective unconscious, and on the other hand, establishing a divine connection with the collective unconscious. It is with the Gnostic that Jung’s metaphysics and systematization really go to the toilet because he saw that every alchemist had a different kind of cryptic language and systematization, and that the essence of what they were trying to say isn’t in the language at all, but in the direct experiencing of Gnosis, a type of ineffable, pre-propositional, pre-symbolic, esoteric knowledge, which helped each alchemist simultaneously individuate and find their own way back to the source of meaning and intelligibility in the collective unconscious.

Long story short, I think Peterson has largely inherited Jung’s orientation. He and his hero are not on an intellectual path but a mystical one that seeks to individuate the psyche and establish a divine connection with the Motherland.

Peterson’s mistake I think isn’t with his metaphysics or lack therefore. The mistake is for him to be out in the wide open with his personal mystical project. I guess “P-God” is quite appropriate also because it is also a Personal God. The mistake is to confuse the esoteric Personal God with the exoteric almighty and all perfect God. The atheists and theists play the exoteric game, which involves putting out one’s propositions about the almighty, all perfect God out in the open and debate their existence and their validity. But Peterson and Jung are playing the esoteric game, not involving propositions or facts about the world or properties of the almighty exoteric God, and therefore not suitable for public debates. I think this confusion makes Peterson foolish. Jung and the alchemists in contrast were much wiser in being private and personal about their esoteric work. Many asked for their work to be destroyed after death because they understood that the nature of their work is so esoteric that they will be inevitably misunderstood. Peterson is foolish precisely in the sense that he confusingly brought the esoteric game to people playing the exoteric game.