The ethical ethicist, Dietrich Bonhoeffer

The problem at the bottom of ethics; the ultimate and penultimate

– 8 minute read time –

A 2014 study published in Philosophical Psychology asked whether ethicists were, on average, more ethical. The results were mixed, but broadly speaking, they concluded professors of ethics were not more ethical than the general population. That’s disconcerting.

Maybe, we should start backwards—find someone good and see what they come up with regarding ethics. Here, we encounter our first problem: According to our cynical age, good people don’t really exist.

While everyone fails, some do an exemplary job of standing against the evils of their time and who, additionally, don’t fail in an outstanding, repugnant way. This qualifies countless quiet, everyday folks lost to memory, but it also includes some famous moral teachers. Siddhārtha Gautama (the Buddha), Jesus of Nazareth, Mohandas Gandhi, and many others qualify, but I want to focus on a German scholar named Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

The “Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy”

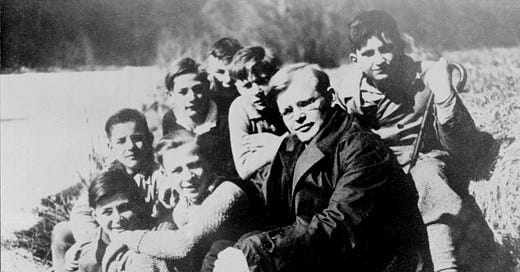

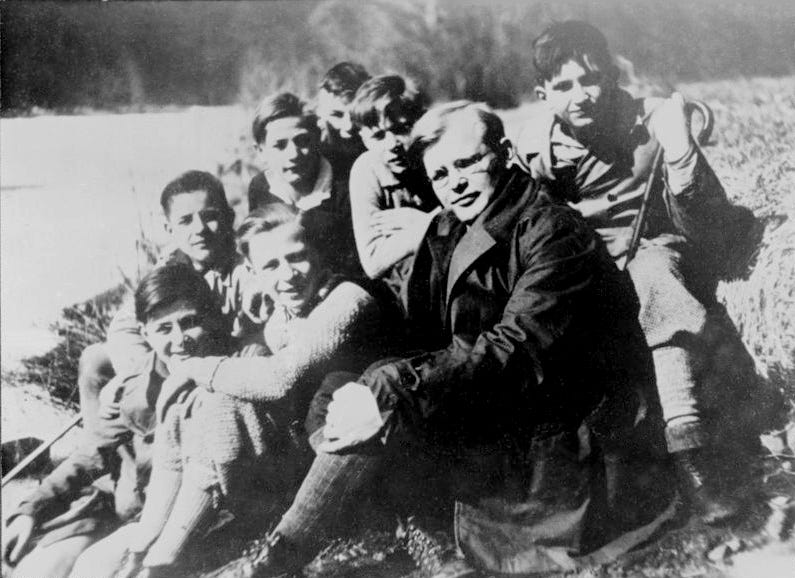

Bonhoeffer was a German pastor, theologian and, in my book, philosopher. Born to a wealthy, large, and well-connected family in 1906, Bonhoeffer enjoyed an intellectually stimulating childhood. His father was a brilliant psychiatrist, neurologist and, interestingly, an agnostic. His mother was a teacher and Christian, with renowned artists and theologians in her lineage.

Bonhoeffer enjoyed a classical, well-rounded education. He composed songs at eleven and retained a passion for the piano his entire life. He quickly rose in the ranks of academia, graduating with a doctorate summa cum laude at the age of twenty-one. I recommend the exceptional biography, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy to anyone interested in his life (and you ought to be).

Now, I know what you’re thinking: A German academic born in the early 1900s who didn’t defect to America? Foreboding. Tread with caution.

As you likely guessed from the title of his biography, Bonhoeffer was not a Nazi. Instead, at multiple crossroads, he chose to stay in Germany to resist the Nazi infiltration in the German church. He refused a coveted academic position in the US in the ‘40s. Rather than accept an offer to study non-violent resistance with Gandhi in the ‘30s, he chose to live non-violent resistance. He joined an underground conspiracy against Hitler, helped Jews escape to Switzerland, and persistently, deceptively, and craftily undermined the Nazi infiltration into Lutheranism.

So, I think we’ve found a pretty good person. Luckily for us, this acute scholar with breathtaking integrity wrote a magnum opus called Ethics (sadly unfinished).

Let’s leave Bonhoeffer aside for a moment to consider a thorny philosophical dilemma he’ll aid in.

The problem at the bottom of ethics

I could talk about this dilemma in a myriad of ways, but, essentially, there is a problem in the “is” versus the “ought” in ethics (cf. David Hume). Maybe we could contrast the ideal and the deal (as in, “here’s the deal…”).

Ethics seem to exist as an ideal rather than a description of what is in reality. With this understanding, a problem arises: where does the moral ideal “come from?” As far as I can tell, there are three main positions.

Ought does not exist; moral codes arise by chance and reduce to matters of taste, instinct, affect, or power. This is, roughly, called moral anti-realism. Hume and Nietzsche seem to be moral anti-realists of some kind.

Ought emerges from the natural world as an emergent property, like software from hardware. Adultery really is wrong, but only contingently upon the way social evolution selects for single mate partnership. Many popular thinkers like Jordan Peterson ascribe to this view.

Ought originates from outside the natural world, but still exists—morals are, but not in a material, physical way. Plato, for example, believed there were higher, transcendent forms that existed out of necessity, like goodness (or justice), truth, and beauty. Actions are morally good insofar as they participated, mysteriously, in goodness. Theists, Christians, believe that the “ought” originates, or co-eternally originates, with God.

Even on (3), a problem remains: how to apply a perfect standard in an imperfect world. There’s more than just an ontological problem here (i.e., how the moral “stuff” interacts with the physical “stuff”), there are infinite ethical problems left to unravel in action itself.

The ultimate and penultimate

I might delve more into this problem in a later essay about “wisdom as ethics.” For now, I want to talk about Bonhoeffer again. In Ethics, Bonhoeffer uses two terms to discuss the two realms of ethics, the ideal and world, as the “ultimate” and “penultimate.”

In context, Bonhoeffer discusses the ultimate and penultimate through the lens of “justification,” a fancy theological term referring to the transference of goodness and rightness with God to undeserving humans. Before justification, everything goes through a penultimate phase—a journey toward the ultimate justification. Paul went through a period of persecuting Christians. The thief on the cross presumably, well, thieved. Both arrived at justification through different means.

Now, the penultimate gains value only through the ultimate. “The penultimate… remains, even though the ultimate entirely annuls and invalidates it.” The ultimate brings with it a finality; there’s no going back. It is in a split moment, and, simultaneously, eternity, that God justifies.

However, “the way from the penultimate to the ultimate can never be dispensed with,” because otherwise, grace would become “venal and cheap. It would not be a gift.” Indeed, “For the sake of the ultimate, the penultimate must be preserved.”

So, we all must travel through the penultimate, hopefully, to the ultimate. This begs the question: If the realm of God, and all that is ideal, is the ultimate, how do we live in a penultimate reality in light of the ultimate?

Radicalism and compromise

Bonhoeffer contrasts two extremes:

Compromise is the “hatred” of the ultimate. This leads to a rejection of God’s judgement and his terminal, supreme, eternal moral wisdom.

Radicalism sees the penultimate and ultimate as mutually exclusive and only knows the law, God’s judgement, and not his mercy. It knows no gray areas, only absolutes.

According to Bonhoeffer, compromise is an unacceptable extreme—far from a praiseworthy middle ground. He elaborates,

“Radicalism hates time, and compromise hates eternity. Radicalism hates patience, and compromise hates decision. Radicalism hates wisdom, and compromise hates simplicity. Radicalism hates moderation and measure, and compromise hates the immeasurable. Radicalism hates the real, and compromise hates the word.”

It’s clear to see that “both alike are opposed to Christ.” These two poles get some things right in their own way, and they’re useful categories in themselves.

But, what is the solution? Not striking a “middle ground,” for that is compromise. Rather, to Bonhoeffer, only Christ can be the solution to this profound impossibility, this paradox at the bottom of morality.

The third way, through Christocentrism

Jesus came into the world as a human, and only through his moral perfection and, yet, suffering, can the ideal (ultimate) and flawed (penultimate) be brought together. Upon Christ, the fullness of imperfection and the subsequent deserved judgement (ultimate) came to be in the world (penultimate). If it stopped there, the penultimate would overtake the ultimate—only through Jesus’s resurrection can the world (penultimate) be redeemed (ultimate).

It is in this way that I agree with Bonhoeffer that only through a “Christocentric” philosophy can we understand ethics as both in the world and yet, of something transcendent. Following the incarnation (the embodiment of God), death, and resurrection of Jesus, we can understand the gap between the ethicist’s actions and the ethics itself—anything else is a woefully incomplete picture.

Without judgement, ethics collapses into an empty, “it is what it is.” Without humanity, without impossible ethical positions (like living as a German in 1940s Germany), there is no weight to goodness, nothing significant about redemption and grace.

So, how to act?

First, follow Christ.

Second, read Ethics with me, and consider reading about Bonhoeffer’s life. He spent his life dedicated to abstractly/theologically, and concretely, in action, weaving his way through unsolvable ethical dilemmas. In Ethics, Bonhoeffer expands on these two realities, the penultimate and ultimate, I can’t delve into it more now. But, chiefly, he lived this good, complex ethical vision—unto death.

Bonhoeffer didn’t condemn his peers who went to fight in the war for Germany; he was privileged enough to put off conscription. But he also didn’t stay silent, he worked with co-conspirators to smuggle Jews and overthrow Hitler. He lied, many times, and would publicly heil Hitler for deception’s sake. He made friends with his captors. He fell in love and died while engaged to his young bride, yet he founded a monastic-inspired, underground seminary. He loved athletics, Ping-Pong, theater, and film, yet held to a (more or less) orthodox, Protestant view of Christianity.

Bonhoeffer never finished Ethics because his ethics put him in a Nazi prison, and later, a concentration camp, where he was executed by hanging at the age of 39. Bonhoeffer’s execution by the Nazi’s for his resistance is a kind of accolade, the sort of thing “treasure in heaven” refers to.

If we should listen to anyone about the ultimate and penultimate… well, it would be Christ himself, of course (cf. Matthew 5-7).

But, maybe as a close second, we should listen to Bonhoeffer, the ethical ethicist.

Soli Deo Gloria

—

This essay is dedicated to my good friend Cole Smith, who tells me the gap between the high standards of ethical philosophies and the impossibility of actually living them out troubles him. I hope you forgive any inaccuracies in my representation of the philosophy of ethics generally, and that this essay challenges you.

[Edit: I made two small changes for historical accuracy and clarity, 10/20/2024]

Good read. I don't know much Bonhoeffer, but I do know that he was deeply influenced by Barth. Barth's view of soteriology--which extends to ethics--is inextricable form his view of history and eschatology. To put it simply, there is an emphasis on the immanent (or penultimate dimension to borrow your terminology) that must see itself as necessarily contingent on but simultaneously towards the transcendent (or ultimate). Commentators coin this term as a dialectic existentialism. I can smell this in Bonhoeffer, but what do you think? It reminds me also of Jurgen Moltmann's soteriology--God suffers alongside us insofar as to embody the totality of suffering towards an authentic salvation. Kenosis is not enough--there has to be the encounter of the immanent, phenomenological experience of suffering. The dialectic Christians sidestep this issue by saying that the logic of dialectics do indeed encounter all possible permutations of suffering by virtue of its being universal, transcendent, and absolute. However, circling back to your article on reductionism, could it not be also that each individual experience of suffering is a quantitatively immeasurable phenomenon onto itself? A self-contained universal among universals, perhaps? (Of course this would call into question the position the status of penultimate relative to the ultimate, so this necessitates the need for reframing the ethical roadmap in its entirety). Bonhoeffer's view posits something along the lines of not so much a mutually contingent dialectic, but maybe a reflexive, self-referrential one along the lines of Kierkegaard. Analogous to kenosis, could it be that the penultimate is a mere modality of the ultimate, which instantiates itself reflexively in order to manifest itself as other? Thoughts?

Also, let's not forget the African bull elephant in the room--there seems to be a lot of emphasis on *work* in Bonhoeffer's theology. Rendering the ultimate manifest vis-a-vis the penultimate. Isn't that just dandy? There's a theology of Christians functioning as catalysts and agents of making the kingdom manifest in both an empirical and spiritual sense. I'm tired of all these non-action evangelicals that vibe and just hope God will figure out and act on his salvation plan, and we're along for the ride. The context Bonhoeffer exists in speaks to the necessity of historical agency. This is a theological trend that was popular amongst 20th century theology in continental Europe it seems, as most of them were quite privy to dialectic readings of eschatology and its relation to all facets of Christian life. Isn't that so badass? That we're not merely along for the ride? We're not driving, but we sure as hell could help in planning the route. Wolfhart Pannenberg's dialectical eschatology and Hans Urs von Balthasar's theo-drama come to mind. I'd love to see if Bonhoeffer's ethics are compatible with these ideas.

https://preview.redd.it/adt05b807zu61.png?width=640&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=248ce278e9a0c552158e816ca34dd9c3f578f09f

Just stumbled here by accident, and only wanted to note two things.

"He joined an underground, anti-Hitler group called Abwehr..."

-The Abwehr was part of Germany's intelligence apparatus, it's military intelligence service, and was not an "anti-Hitler group." From what I can gather, most biographers describe Bonhoeffer as joining as a "double agent" who gathered and shared information to help the Allies and those in the resistance.

- Wilhelm Franz Canaris, who led the Abwehr while Bonhoeffer was an agent and was executed awith Bonhoeffer, had long been a murderous extreme German nationalist since immediately following WWI, helped organize the Freikorp, and was enthusiastic in his support of the Nazis and Hitler's regime including it's anti-Semitism until the late 1930s. Canaris' opposition and involvement in plans to overthrow Hitler did not reflect the same kind of ethical stance or commitment one finds in Bonhoeffer or other members of the resistance, and his execution hardly would merit the name "accolade." Like other former and perceived former Nazi loyalists, he reaped what he sowed.