"Warfare" is Ethically Different from other American War Movies

"Warfare" Honors Veterans without Glorifying the US Military

Ray Mendoza and Alex Garland’s Warfare isn’t a normal war movie for a few reasons.

It’s presented in real time.

It’s co-directed by one of the soldiers featured in the film (Mendoza).

The sound design is jarringly realistic.

The audience learns nothing about the personal lives of the soldiers.

By my count, only a single enemy combatant is shown shot on screen.

Let’s unpack these, and other, of its unique stylistic choices, and how this reveals an ethical difference between it and other war movies.

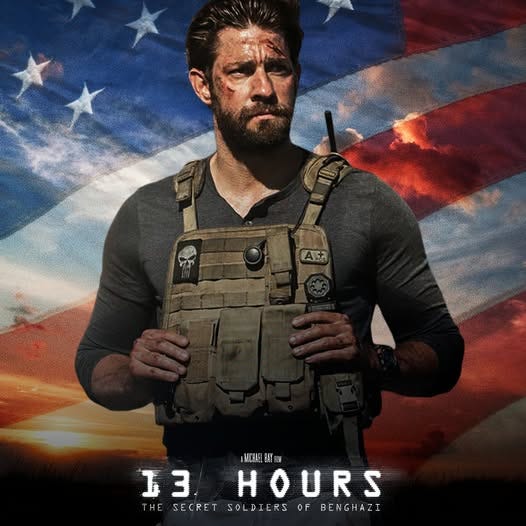

Compared to “Black Hawk Down” and “13 Hours”

To begin, I’ll contrast Warfare with a couple of other modern films in the sub-genre we might call, “true story get the hell out of there” war movies: Black Hawk Down and 13 Hours. On the surface, all three films are similar:

American soldiers are stranded in enemy territory, and must escape, protecting their own along the way.

American soldiers are on the back foot—they’re without a plan and with little to no support.

American soldiers display the immense bravery of modern-day warriors, trying to protect their own wounded and innocents amid violent chaos.

American soldiers are shown on screen with grisly, unimaginably hellish wounds—often mortal injuries.

The American soldiers are elite special forces. (Rangers, retired seasoned military, and Navy SEALs.)

Finally, all three movies are based on true stories, straight from the memories of the American soldiers.

When I watch war movies, I’m usually inspired by the soldier’s courage. Outnumbered, often bucking against their orders, without support, the elite units manage to pull through. I’m also aware that the violence is horrific and often pointless.

However, there are poignant differences between most war movies and Warfare. Let’s hone in on certain elements of movies like Black Hawk Down and 13 Hours.

The Focus of American War Movies

First, I’ll present some common themes or focuses of these movies.

Guns and Kit

Modern war movies often include scenes of soldiers “suiting up.” There’s a tactile, almost sensuous focus on the kit—the guns, ammunition, armor, helmets, night vision goggles, and more, which, by one calculation, adds up to around $40,000 or more. In several dark shots, the soldiers have an almost robotic or alien quality, otherworldly in power and violence, like angels of death.

Undoubtedly, this is cool. Anyone who says guns and kit aren’t cool is lying.

Competency and Confidence

American soldiers are also shown as maximally competent (most of the time). They’re exceptionally skillful—the best in the world in the craft of killing. Special forces cost half a million dollars to train. They are in peak physical condition. They stay calm and confident in the most utterly devastating situations.

Their training kicks in, and, like machines, they can double tap humans souls out of bodies with maximum efficiency.

Boyish Bonds

And, of course, don’t forget the almost constant adolescent joking. Sometimes, it’s lighthearted and very, very human. Other times, it’s overplayed and stereotyped to the point of silliness.

The war movies, usually, then, attend to competency, confidence, camaraderie, and equipment—the pinnacle of masculine power. Despite the American soldiers being on the back foot, these two movies mostly protect this powerful image of modern soldiering. There’s another element to consider.

Killing

There’s another emphasis in Black Hawk Down and 13 Hours: The raw number of enemy combatants killed.

I don’t doubt the accuracy of the portrayal of the relative effectiveness of American soldiers in these combat settings. Rather, the way Michael Bay (known for his explosions) lingers on Benghazi terrorists being mowed down, with fireworks-like detonations, and Ridley Scott (known for slow-motion fight scenes) shows countless enemies tagged, set up and knocked down, is a stylistic choice.

Of course, violence is shown. It’s a war movie, you might reply. The sight of killing enemy combatants is not an indictment of these films, per se. There’s more to unpack.

American War Movies and Awe

The coolness and effectiveness factor, plus the genuine bravery, plus the raw numbers of enemies killed, all combine to evoke awe.

I did my philosophical research on wonder. Awe is a similar phenomenon.1 It transforms our picture of reality to accommodate greater power than we thought possible, whether witnessing a tornado, a miracle, or shooting a .50 caliber something at something else (which I’ve done), awe coincides with power.

Americans often make fun of authoritarian countries’ massive military parades, like North Korea, China, Russia, and others. These are designed to evoke awe. Why? Awe draws worship and submission, gives hope of victory, swells nationalistic pride, and alleviates fear.

In short, awe affords the powerful more power.

American war movies are our version of military parades.

This isn’t a conspiracy theory. I’m certainly not criticizing or condemning our veterans. I don’t even know if these choices by Scott and Bay are “deliberately” evoking awe of the US military or if these directing choices make for a more entertaining thriller. Aside from this, humans are story, narrative-driven creatures. Greek tragedies can help veterans process their PTSD.2 War, most of all, needs structure to process.

However, it’s clear to me: The US doesn’t need to conduct military parades because of American-produced war movies.

“If my guys, stranded and without support, can do that to the other guys, I’d say we’re doing pretty good!”

“Look at our tech, training, bravery, and efficiency—no one can stop America.”

There’s something even more sinister I feel when I watch these war movies. I’ve observed, in myself, an immense, emotional satisfaction when the “bad guys” are killed in large numbers. I think, “They may have killed a few of our guys, but we killed hundreds of theirs!” It’s akin to the satisfaction of karma or revenge.

It’s the pleasant sensation of large-scale violence done to those who are set against my tribal group (the US).

It’s not a good look for me, but I doubt if humans can help it.

“Warfare” Doesn’t Inspire Awe—Good!

Warfare takes a different tack.

In their stylistic, directing choices, Mendoza and Garland avoid evoking awe. Warfare gives no satisfaction. It shows the war as it really is. Iraqi veterans across the internet confirm its adherence to realism.

For clarity: This is not an antiwar movie per se. Aside from this, I’m not a pacifist. Warfare isn’t even political (certainly not as political as 13 Hours, or We Were Soldiers, for example.) It’s directed by a veteran and dedicated to Elliott Miller, who lost his leg and voice in the attack.

Warfare is a stripped down war movie that stands as a damning mirror to other war movies. If you watch Warfare, I doubt you’ll watch other war movies the same way. The drama, narrative, epic crescendo of the others will feel out of place and mismatched.

While other films show the horrors of war, Warfare doesn’t let you look away or smooth it over with an epic score by Hans Zimmer. There’s a long, drawn out sequence of the platoon scrambling, where one of the men is screaming in pain. The screaming does not stop for many long, long, drawn out minutes. There is no cut to relieve the audience. It grates like nails on chalkboard.

Their officer breaks down and cannot give orders.

The soldiers are frantic and don’t know what to do.

They can’t apply a simple tourniquet due to shaking hands.

They accidentally stab themselves with morphine.

They stare with dead eyes in clinical shock.

Even displays of power by the US military in Warfare don’t even really evoke awe (tanks obliterating buildings and low fly overs by fighter jets). They’re used in a desperation, and don’t seem to deter the enemy fighters.

Bombs, grenades, and gunfire are sudden, shocking, and instantaneous.

There are few cinematic shots.

There’s no score.

Explosions shake the theater.

It’s claustrophobic and stressful—violence stripped of structure or narrative.

But, and this is important, that doesn’t erase the soldier’s bravery. In fact, it elevates it.

In short, you should watch Warfare. It’s undramatic, unepic, and un-awe-inspiring in all the right ways. You’ll never see another movie that, unwittingly or not, glorifies the US military the same way again.

Soli Deo Gloria

To any veterans reading, thank you, for your service. I hope Warfare, and this essay, honors you.

I’ve linked to a Fisher House, a charity that helps lodge and transport veterans and their families while they undergo treatment and help. It’s a well-established, above-board non-profit.

Feel free to link to others, as long as they’re well-established, in the comments!

https://fisherhouse.org/

Yaden, David Bryce, Jonathan Haidt, Ralph W. Hood, David R. Vago, and Andrew B. Newberg. “The Varieties of Self-Transcendent Experience.” Review of General Psychology 21, no. 2 (June 1, 2017): 143–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000102.

The Theater of War: What Ancient Tragedies Can Teach Us Today, Bryan Doerries, 2016.

I think your "kit" number must be low, wherever you got it... but I know that is not the point, I am just teasing... I am intrigued to see the movie. I think the 13 hours, Blackhawk Down (and their predecessors and contemporaries, like Lone Survivor, American Sniper) are also trying to show the responsibility America has bc of our technological superiority and our ability to take lives... but that may be a read through the lens of your great-grandfather, Hop. But overall, I totally agree with the way our movies, even when they are nuanced, are also glorifying (even when accurate) in their presentation of the American Military. I also think that there is another piece that is intriguing - what if it were a less "noble" minded nation that had this superiority - could it be one of the thing that we are glorifying is the way that America might could defeat any other military, but doesn't?